Quite often, I will make analogies to residential home construction, particularly as I am familiar with in East Tennessee in the US, working with my dad’s construction crew nearly two decades ago among the mountains not far from one of the entrances to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Building houses on the side of a mountain is not easy.

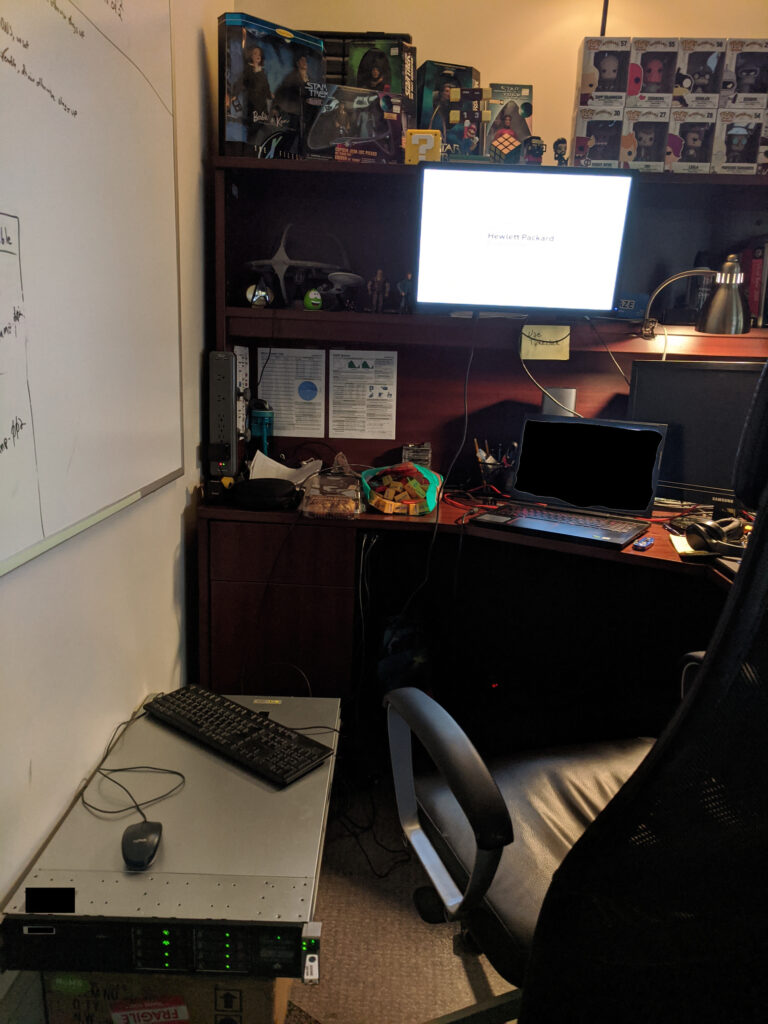

I have said that a hypervisor is akin to the concrete foundation, but the times I have said that have been to underscore the importance and role of a hypervisor. When looking holistically at the core components of IT infrastructure (compute, network, and storage), a slightly better picture emerges. The servers, various network equipment, storage arrays, etc. become the foundation. Hypervisors then become akin to the framing, or the structural core. The plumbing, electrical, HVAC, and so on are woven among around the framing, and are like an interconnected mix of VMs and services.

In the world of virtualization, many hypervisors exist fulfilling different tasks, operating at different levels, and varying greatly with licensing and other associated costs. For desktop power users like myself who primarily started on Windows, only beginning to dabble with Linux with Ubuntu in the mid-2000s, names like VirtualBox, VMware Workstation, and Parallels should be quite familiar. These were/are applications that required installation on top, and ran inside, of Windows (or MacOS in the case of Parallels). This is what is called a Type 2 hypervisor. VirtualBox and VMware Workstation were typically free to download and use for non-commercial use, and sometimes even that was permitted. Parallels has typically come with a small one-time cost. Since Type 2 hypervisors are installed on top of, and shares resources with, an existing OS, virtualization here is typically a supplemental use-case for any single computer. Of course, they are useful for light testing of different operating systems, whether for development purposes for test driving a new distro of Linux. While they can be used for hosting lightweight servers, they are not the most ideal due to the resource burden on the host, and lack of backup solutions compared to more dedicated (most often Type 2) hypervisors.

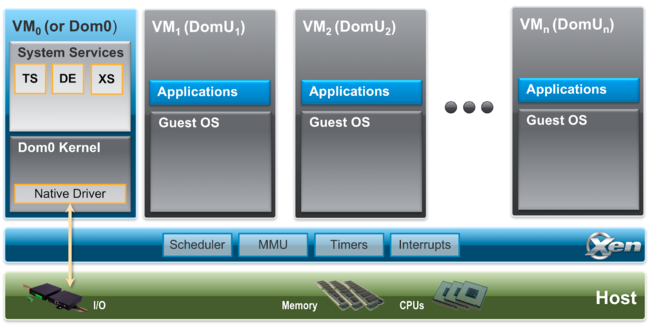

That brings me to Type 2 hypervisors. The most familiar names here are things like VMware, Hyper-V, Nutanix (specifically with their AHV, or Acropolis Hypervisor),and Xen. Looking closer at Xen, it comes from the open source XenProject, and dates all the way back to a research project at the University of Cambridge in 2003. It powers large aspects of the automotive and embedded industries, provides the hypervisor core of Citrix XenServer and XCP-ng, and has been a fundamental part of AWS’ virtualization elements since the beginning. Type 2 hypervisors are typically considered bare metal, where they are installed directly on a host and have exclusive access to hardware resources.

Long story short, hypervisors allow you to run a bunch of servers (virtually) inside your server (bare-metal).

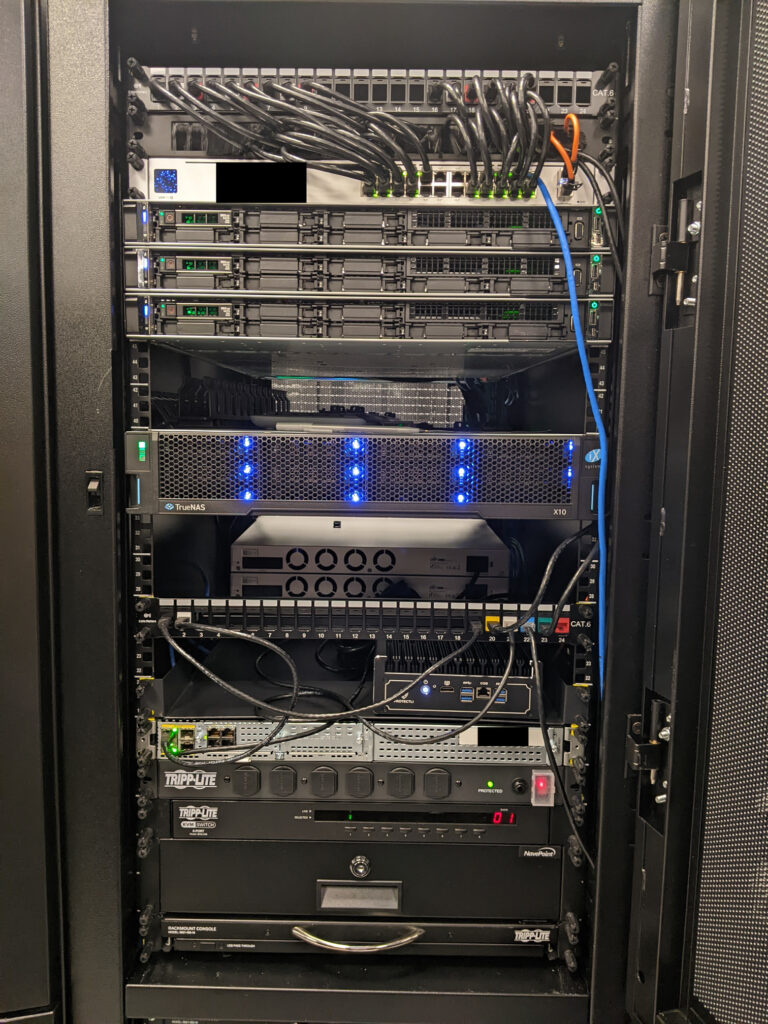

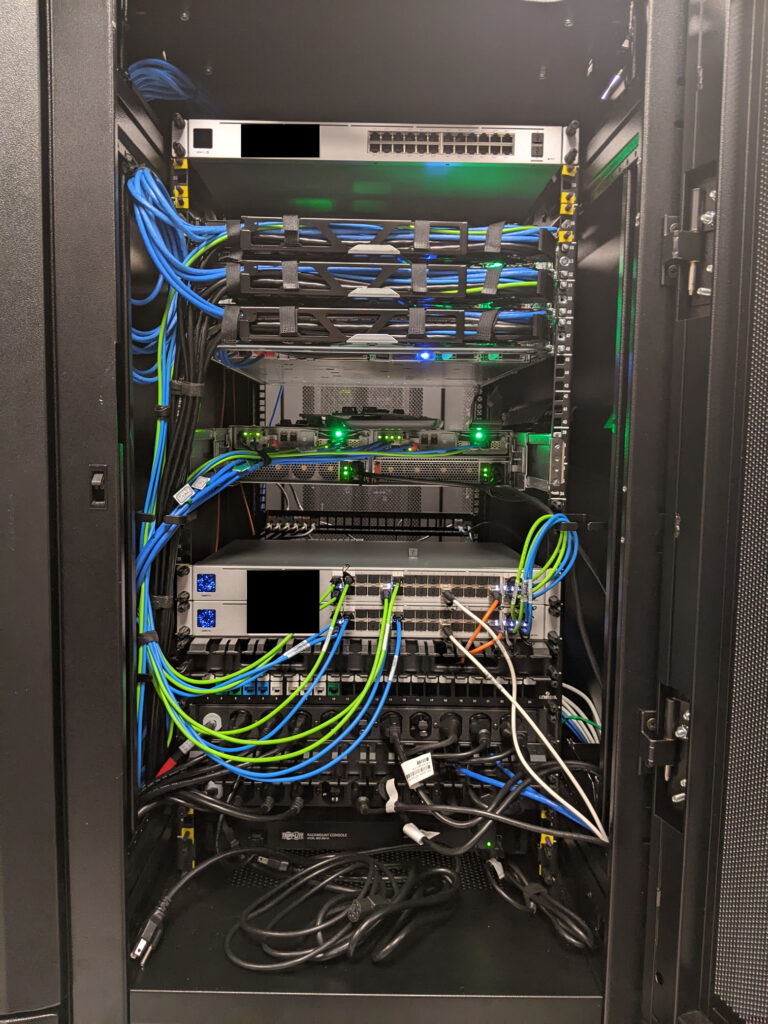

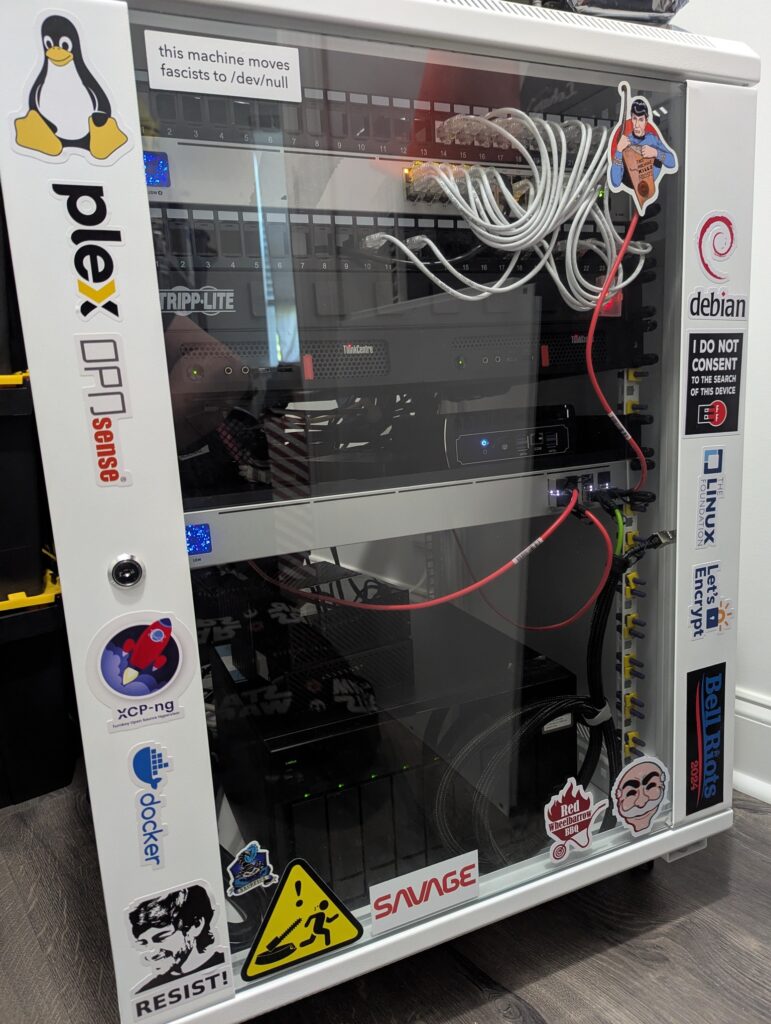

VMware, Hyper-V, Nutanix, as well as XenServer come with their own additional, often very high, licensing costs. XCP-ng and Proxmox VE are (FLOSS, or free and libre open source software) and can both be downloaded, installed, and used in a homelab or production for free, with only the restrictions of their open source licenses. Additional enterprise support subscriptions are available for both. The rest of this post will focus on XCP-ng and Proxmox VE.

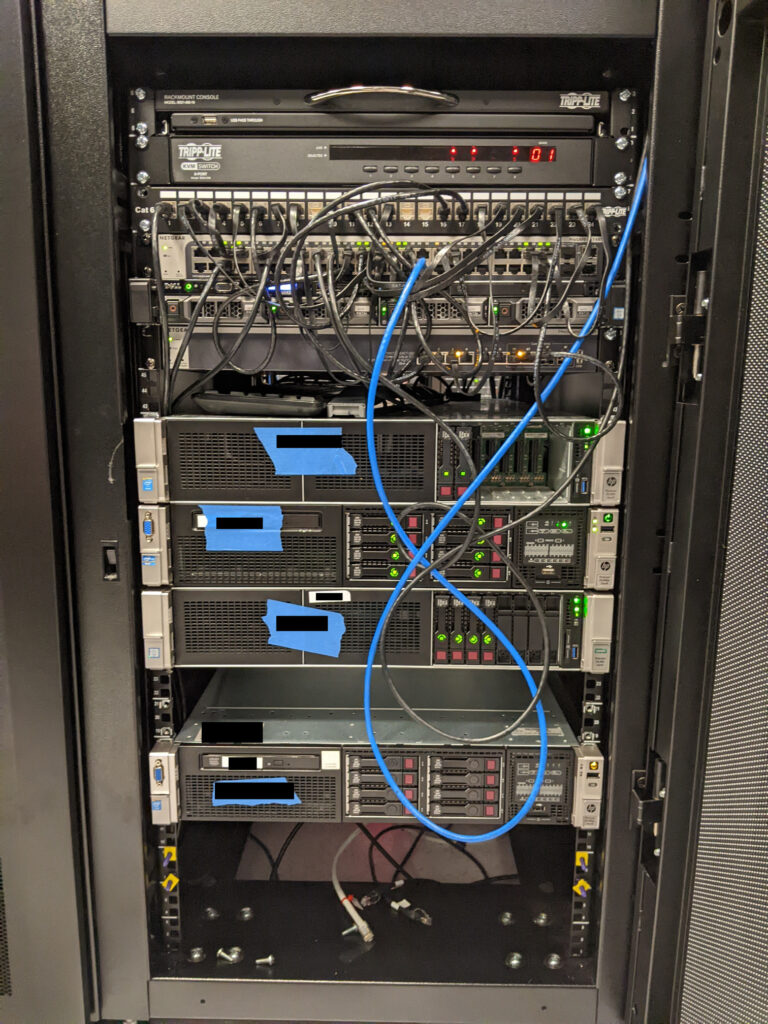

The beauty of XCP-ng, in particular, is that it is quite capable whether installed on a dusty old spare workstation that was stuffed in a closet, or installed on a series of critical high performance compute nodes in a data center environment, all while being free and open source. Sure, Proxmox VE (and by proxy KVM) can also do this, but my experience (and bias) is with XCP-ng. One reason I did not adopt Proxmox years ago was that while KVM may often be talked about as a Type 1 hypervisor, it is actually a Type 2 as it relies on Linux kernel modules for virtualization. In the case of XCP-ng, Xen is booted first with exclusive access to hardware, and then a special Dom0 VM is booted with privileged access to that hardware. The Dom0 VM provides a secure bridge between user-created DomU VMs and the Xen microkernel. For homelabbers, this kind of distinction may be like splitting hairs, but as I was first adopting for production use, and this sort of security isolation was extremely important.

Borrowing from The Myth of Type I and Type II Hypervisors:

“The most common definition of “type-1” and “type-2” seem to be that “type-1” hypervisors do not require a host Operating System. In actuality, all hypervisors require an Operating System of some sort. Usually, “type-1″ is used for hypervisors that have a micro-kernel based Operating System (like Xen and VMware ESX). In this case, a macro-kernel Operating System is still required for the control partition (Linux for both Xen and ESX).”

Somewhat often, I will see posts from users on Reddit (or elsewhere) on how Proxmox VE is the better hypervisor, or it simply better for the homelab, than XCP-ng, but I rarely ever see anyone explaining why they think that way or what they are ultimately hoping to accomplish. Without additional context, the Type 1 versus Type 2 comparison is not immediately useful here. In a sense, Proxmox VE and XCP-ng both do rely on Linux, and the Linux kernel. Proxmox VE is essentially a Linux distribution with a focus on virtualization. This is especially attractive to homelabbers who like the “everything but the kitchen sink” approach with being able to deploy VMs, containers, etc. within the OS, as well as modify the OS to their liking. XCP-ng, and Xen, is built on a very different philosophy, one where VM are the entire focus, and where the Dom0 Linux VM should not be modified. Proxmox VE users are used to anchoring everything directly into the metaphorical concrete foundation, whereas XCP-ng urges users to build out from the metaphorical framing, and beyond. Sometimes it is good to let your hypervisor just be a hypervisor, or your storage just be storage, or any other version of that.

One large reason people choose FLOSS projects is to try to avoid vendor lock-in, or where they become so dependent on a vendor’s product(s) that it often becomes extremely difficult or costly for them to switch to a competitor. Vendors are quite aware of this and will often take advantage by raising prices. Using Proxmox VE with that approach introduces another kind of lock-in, where a loss of a host can have catastrophic consequences. To be fair, the same can be true of XCP-ng to a certain extent, especially if VMs and config only reside on local storage and that is also lost. In an environment with multiple hosts in a pool and shared storage, ideally where each host has identical hardware, each XCP-ng host becomes easily replaceable. If for some reason XCP-ng is not working on a host for whatever reason, and it becomes more trouble than it is worth to continue troubleshooting, simply wipe, reinstall, and rejoin to the pool. The host will be resynchronized with the pool config, including network and storage config. This way, each host is thought to be ephemeral. If only repouring a new concrete foundation under a house were that simple.

Following those thoughts, I have noticed there seem to be two different (although not mutually exclusive) ideas when it comes to how folks perceive their installed hypervisors, both in professional and homelab settings. On one extreme, an installed hypervisor is seen as critical and sacred, and great effort is spent to ensure each install never fails, and a lot of time may be spent troubleshooting problems if they do happen. This is certainly a perfectly valid perspective, and I have most commonly seen this with mission critical scenarios, for hosts with non-replicated local storage, and in homelabs with Proxmox since those users may find the “everything but the kitchen sink” approach useful.

On the other extreme, there is the concept of ephemerality. Applied broadly to the entire environment, it would mean that every possible layer of infrastructure has potentially multiple redundancies, not just for load balancing, but to make painless and zero (or extremely minimal) impact any failures within those layers. When applied solely to the hypervisor, you have the flexibility that I mentioned above with XCP-ng. If each host is a member of a pool with identical hardware and shared (or replicated local, in the case of XOSTOR) storage, then replacing a host should approach trivial (if not being entirely trivial). With enough redundancies across the pool, the temporary loss of a single host should not be felt by a single user.

Of course, these are two extremes, and each user’s approach is going to lay somewhere in the middle.

Now, to be fair, during writing this I decided to install Proxmox VE on one of my hosts since they are currently down until I rebuild my XCP-ng pool. Even though I am writing at a mostly high level about both, I felt it could be seen as disingenuous if I did not at least try Proxmox VE. Two hurdles popped up almost immediately. First, the graphical installer does not seem to like 720p, which is the default resolution of the PiKVM V3. The text mode installer did work fine, though. Second, was when configuring the management interface during the install, and it did not seem to give the option to set a VLAN tag. Why did I not just set the native VLAN on the switch port? Well, because I should not need to do that, and because in the (extremely unlikely) event that someone gets physical access and plugs into the port, I would prefer them not to be put directly on my management VLAN. Sure, I could mitigate this with allowed MACs or whatever else, but none of that should be necessary. Since Proxmox VE is a virtualization/containerization-focused Linux distro, it was simple enough to set the VLAN tag in /etc/network/interfaces after it booted for the first time. I doubt I am alone in thinking this way, and since Proxmox VE dates back to 2008, they really have no excuse here. After install, I went so far as installing an Ubuntu VM, but I did not go much further. My initial impression is that so much of the design decisions do not make a lot of sense, like it was just bolted together from nearly two decades of technical debt. I really had no intention of being unkind, but I do intend to take at least another cursory look some time in the future after rebuilding my XCP-ng pool.

One more maybe worth mentioning for the scale of SMB or homelab that I have experience with is Harvester from SUSE. In fact, I had looked at it just before XCP-ng back in maybe 2019-2020, but XCP-ng was far more mature at the time. I doubt I will switch from XCP-ng any time soon, but if anything could make me consider it that may be Harvester.

Put simply, virtualization is about redistributing hardware resources that may otherwise be wasted, and has become a fundamental component to most any computing environment, both large and small scale.